The feeling I get when I contemplate the origins of science fiction is similar to what I felt as a kid when I asked, “Then, who created God?” And whenever I read a very old science fiction story I wonder if its science fictional ideas were original to that story, or had an even earlier writer originated those concepts? So far, it’s been like the famous Carl Sagan story, it’s turtles all the way down. Was there ever a Big Bang beginning to the science fiction universe? Go read The Book of Genesis. Isn’t the story of Noah a post-apocalyptic tale of science fiction? Don’t the stories of the Garden of Eden feel like science fictional speculations?

People and writers have always pondered the past and future in ideas that are now considered the domain of science fiction. I used to believe that science fiction couldn’t have existed before science, but then when did science begin? I’m sure flint chipping took a lot of experiments, statistics, and testing to perfect, which makes me wonder about our cave dwelling ancestors and what they imagined.

When I read an older science fiction novel now I like to imagine how the readers of its time thought about the ideas used within the story. For example, I just finished The Clockwork Man by E. V. Odle, first published in 1923. The story is about a creature that appears suddenly at a cricket match. It looks human but acts strange. During the course of the story we learn its from eight thousand years in the future and it’s something we’d call an android or cyborg today.

From my Scribd subscription I listened to the HiloBrow audiobook edition of The Clockwork Man, part of their original Radium Age of Science Fiction Series. A Summer 2020 note to the site promised to new series from MIT Press beginning in 2022, but there are several editions on Amazon now.

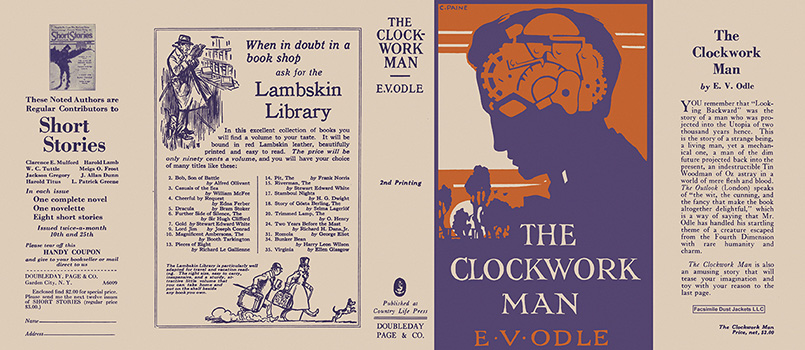

The intro to 2013 edition by Annalee Newitz is here. However, the novel is in the public domain and can be read at Project Gutenberg. Below is a reproduction of the original dust jacket from the 1923 American edition from Doubleday.

At first, when we are introduced to the clockwork man, I believe most modern readers will wonder if he is a robot. But as the story goes on, we realize the people of the period see him as human looking, with an odd bulge on the back of his head, which he hides with a hat and wig. Readers eventually learn that bulge is a clockwork mechanism that controls his biological processes. Not only does it give him superhuman senses, but great physical power, and even the ability to transport itself in time, space, and other dimensions.

E. V. Odle evidently believed in 8,000 years a lot can happen to the human race. The story feels like a comedy of errors at the beginning when this strange creature interrupts the cricket match, but gets more serious and philosophical as the story progresses. By the end of the tale, we have two twentieth century men arguing over whether evolution and technological progress has gone too far.

The essence of science fiction is exploring certain types philosophical questions. However, in every age the current scientific knowledge limits that exploration because the analogies and metaphors to describe the future depend on current technology. In 1923 Odle’s future man is imagined with clockwork technology. This is long before computers. L. Frank Baum imagined a similar mechanical man in Tik-Tok of Oz in 1914. The concept of robots emerged in 1921 with R.U.R., a Czech play about androids, but the idea of a mechanical being soon followed in science fiction in the 1930s. The idea of human created beings goes way back, each using the best technology of the day to imagine its creation.

Today we would consider it silly to build an AI being with clockwork technology. In the 1950s Philip K. Dick imagined robots made with vacuum tubes and tape loops, which we now groan at. Nowadays, we imagine AI beings constructed with computer silicon circuits. Fifty years from now, readers might consider using silicon circuits just as silly as clockwork or vacuum tubes. Remember, God made man with dust, and Mary Shelley had Frankenstein assembled his creature from stolen body parts. Our speculation about the future is always tied to what we know at the time. Reading The Clockwork Man made me think about what E. V. Odle had to work with in 1923.

We’re all quite familiar with all the philosophical issues surrounding robots, AI, cyborgs, and androids since science fiction has dwelled on them our entire lifetime in books, television, movies, and other art forms. But can you imagine how someone in 1923 could have contemplated the concept? Odle imagines new beings emerging from human machine combinations, which we since defined as the territory of cyborgs.

Yet, The Clockwork Man goes well beyond that. This visitor from the future finds 20th century humans rather limited, stuck in one three-dimensional dimension, whereas it can travel in time, space, and through multiple dimensions at will. It sees reality as a multiplicity of states. This is hard for us to imagine, but science fiction has often considered such possibilities.

Reading The Clockwork Man I can feel E. V. Odle struggling to imagine the potential of humanity. The story itself ranges from quaint to quixotic. During the course of the story the visitor from the future is both admired, feared, and pitied. It’s only towards the end does Odle give us a larger vision of the future, one that’s even more science fictional, closer to Stapledon than Wells.

"But must you always be like this?" he began, with a suppressed crying note in his voice. "Is there no hope for you?" "None," said the Clockwork man, and the word was boomed out on a hollow, brassy note. "We are made, you see. For us creation is finished. We can only improve ourselves very slowly, but we shall never quite escape the body of this death. We've only ourselves to blame. The makers gave us our chance. They are beings of infinite patience and forbearance. But they saw that we were determined to go on as we were, and so they devised this means of giving us our wish. You see, Life was a Vale of Tears, and men grew tired of the long journey. The makers said that if we persevered we should come to the end and know joys earth has not seen. But we could not wait, and we lost faith. It seemed to us that if we could do away with death and disease, with change and decay, then all our troubles would be over. So they did that for us, and we've stopped the same as we were, except that time and space no longer hinder us."

I wanted to know more about the Makers. For most of the novel we thought the clockwork man was the epitome of humanity from eight thousands years in the future, but now we learn there are other beings, even greater. I must assume Odle is warning us against taking the cybernetic path, and hints that a greater spiritual one is possible.

I’m not sure 21st century humans have such fears, because we’re racing as fast as we can to invent both creatures of silicon and to evolve ourselves into posthumans. This reminds me of the ending of the film Things to Come (1936) inspired by H. G. Wells:

PASSWORTHY: “My God! Is there never to be an age of happiness? Is there never to be rest?” CABAL: “Rest enough for the individual man. Too much of it and too soon, and we call it death. But for MAN no rest and no ending. He must go on–conquest beyond conquest. This little planet and its winds and ways, and all the laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him, and at last out across immensity to the stars. And when he has conquered all the deeps of space and all the mysteries of time–still he will be beginning.” PASSWORTHY: “But we are such little creatures. Poor humanity. So fragile–so weak.” CABAL: “Little animals, eh?” PASSWORTHY: “Little animals.” CABAL: “If we are no more than animals–we must snatch at our little scraps of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more–than all the other animals do–or have done.” (He points out at the stars.) “It is that–or this? All the universe–or nothingness…. Which shall it be, Passworthy?” The two men fade out against the starry background until only the stars remain. The musical finale becomes dominant. CABAL’S voice is heard repeating through the music: “Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be?”

I read The Clockwork Man because of reading Yesterday’s Tomorrows: The Story of Classic British Science Fiction in 100 Books by Mike Ashley. British science fiction feels like it’s always been more philosophical than American science fiction, which has usually focused on the adventure and action side of Sci-Fi implications. Many of the books Ashley describes from the late 19th and early 20th century are ones I haven’t read. But Ashley shows those books explored science fictional concepts I thought originated in American science fiction during the 1940s and 1950s. I was wrong. I have to wonder, were those ideas original to the British in this earlier era of science fiction? I have another book that I haven’t read by Brian Stableford, The Plurality of Imaginary Worlds: The Evolution of French Roman Scientifique that explores French science fiction in the 1800s. Was France the Big Bang beginning of science fiction? Or will I find another turtle beneath the French?

James Wallace Harris, 4/20/21