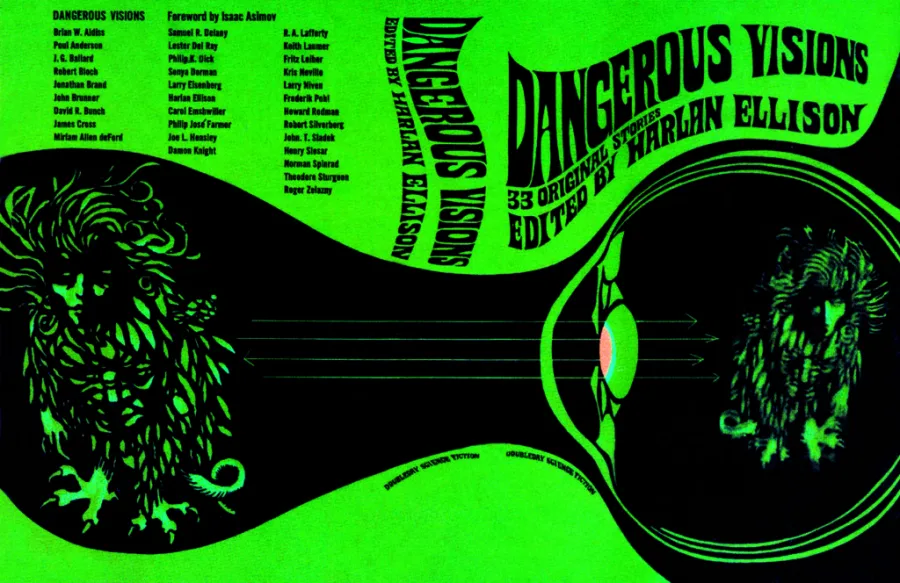

For me, the most rewarding pages of Dangerous Visions were the introductions by Harlan Ellison and the afterwards by the authors. When I first read this anthology back in the late 1960s, I felt those introductions gave me insight into the family of science fiction writers, one I wanted to join. At the time I was sixteen and I totally bought Ellison’s enthusiasm and promises. Fifty-six years later, I reacted to this anthology and its stories very differently.

Ellison honors del Rey by putting his story in the pole position, and he praises his friend and mentor Lester for being a giant of the genre. Back in 1968, Lester del Rey was not a major figure to me. I had read some of his Winston Science Fiction juveniles, but unknowingly, because they were published under his pen names. However, one had his name on the cover, Marooned on Mars. It wasn’t a standout, and I didn’t remember he wrote it. Lester del Rey was not a giant in the field to me. Later on, I’d discover he wrote “Helen O’Loy” and “Nerves” when I read The Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies. I don’t think Lester del Rey was ever a great writer of science fiction, but he became a great editor and publisher.

Ellison hyped Dangerous Visions for publishing stories that editors couldn’t or wouldn’t because they contained ideas that challenged the norms of society, or were too mature for the typical youthful science fiction reader, or were written in creative styles that average science fiction reader would reject.

“Evensong” is about hunting down a fugitive. That fugitive was God. At sixteen that excited my young atheist mind. But at seventy-two, it felt like Mad Magazine’s Alfred E. Neuman saying, “What, me believe?”

Was that really a dangerous vision that no publisher would accept? Then how could Fred Pohl publish del Rey’s “For I Am a Jealous People!” in Star Short Novels in 1954? In that story, mankind is fighting aliens and learns that God has sided with the enemy, so humans declares God is their enemy too. In other words, del Rey gave Ellison a dangerous vision that he’d already used years earlier.

That’s something I keep finding as I reread Dangerous Visions. Ellison was wrong that science fiction publishers wouldn’t take them. It made me wonder if Ellison could have assembled a reprint anthology called Dangerous Visions and collected all the science fiction stories that were published that had been quite startling for the times. Many classics come to mind that I think had more impact than those in Dangerous Visions, such as “Fondly Fahrenheit” by Alfred Bester and “Lot” by Ward Moore. I also think “For I Am a Jealous People!” is a better story than “Evensong.”

Ellison quotes del Rey’s letter to him about the afterward he wrote for the anthology. I thought this part was rather telling:

The afterword isn’t very bright or amusing, I’m afraid. But I’d pretty much wrapped up what I wanted to say in the story itself. So I simply gave the so-called critics a few words to look up in the dictionary and gnaw over learnedly. I felt that they should at least be told that there is such a form as allegory, even though they may not understand the difference between that and simple fantasy.

I was bothered that del Rey didn’t think critics wouldn’t know what an allegory was and couldn’t tell it from fantasy. That suggests del Rey felt a naive self-importance about his writing. But I also felt that Ellison showed a naive sense of self-importance about Dangerous Visions.

Allegory always seemed to me to be lazy way to tell a story in modern times. And I don’t think “Evensong” is total allegory either because we’re told God’s thoughts and perspective. Would John W. Campbell (Analog), Frederik Pohl (Galaxy), or Edward L. Ferman (F&SF) have rejected “Evensong” in 1967 because it was too dangerous? My guess is they would have run it because of del Rey’s name, although they might have rejected it for being too bland and simple in construction. It’s not a very sophisticated story and comes across as something a precocious student would write who was trying to be daring.

In 1967 revolution and rebellion were in the air. The youth of the 1960s were revolting against the status quo. Looking back, I feel Ellison was trying to do the same thing in the science fiction genre. Ellison was loud, outrageous, and pugnacious, so we might consider him the Abbie Hoffman of the science fiction counter-culture.

As I go through the stories in Dangerous Visions I’m expecting to find psychological snapshots of Ellison, the genre, the writers, and the times. The April 8, 1966, cover of Time Magazine asked if God was dead. Had del Rey forgotten his earlier story and “Evensong” was merely a science fiction riff on the Time cover?

Were the writers in Dangerous Visions thinking about old science fiction, or current events? Was Dangerous Visions anticipating the future, or reacting to an already fading pop culture rebellion?

JWH