In 1909 E. M. Forster’s story “The Machine Stops” was published in the November issue of The Oxford and Cambridge Review. It is a dystopian tale about a future society run by a machine. Forster was replying to H. G. Wells novel, A Modern Utopia serialized in the Fortnightly Review in 1904 and 1905. Neither writer thought they were writing science fiction because, first, the term did not yet exist, and second, because Wells was promoting scientific socialism and Forster was protesting it. However, both stories had all the trappings of science fiction.

A Modern Utopia is seldom remembered by science fiction fans, but “The Machine Stops” is considered one of the classics of the genre, and often reprinted in retrospective anthologies of science fiction short stories. When did science fiction fans first discover “The Machine Stops” and claim it for the science fiction genre? And did E. M. Forster who lived until 1970 ever know this?

Many within the genre consider science fiction originating with Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories, first published in April 1926. Gernsback first called these stories scientifiction, but within a few years coined the term science fiction. That term “science fiction” didn’t become widely known outside of the genre until the late 1940s and early 1950s. See my essay, “When Mainstream America Discovered Science Fiction.”

Hugo Gernsback is also credited with creating science fiction fandom by encouraging readers of the stories in his magazines to communicate in his letter column. Eventually, he organized the Science Fiction League in the April, 1934 issue of Wonder Stories. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s science fiction developed as a genre, and readers began calling themselves fans and developed a subculture they called fandom. You can read more about both in these two wonderful books.

However, what do you call stories that use the techniques and themes of science fiction published before Gernsback? What do you call readers who loved these kinds of stories before fandom? Science fiction has always been written by writers who work outside of the genre – before and after it was established. And there were readers before the genre existed that loved stories we now call science fiction.

Science fiction has been laying claim to these proto-SF stories for decades. Gernsback had to reprint Poe, Verne, and Wells in the early issues of Amazing Stories because he didn’t have enough new science fiction to start his magazine. Interestingly, he didn’t reprint “The Machine Stops.” Nor did any of the other pulps that eventually began reprinting classic fantasy and science fiction.

When I reread “The Machine Stops” for a Facebook group that discusses science fiction short stories, I noticed something interesting. Forster describes a future where humans have withdrawn from the surface of the Earth, but automatic aerodromes run by the machine keep the flying machines going on their old routes. This was very reminiscence of “Twilight” by John W. Campbell, Jr., where a time traveler visits a far future Earth and the people have abandoned cities that still function by automatic machinery, including air fields. This made me wonder if Campbell had read Forster’s story. It also made me wonder just when did science fiction fans discovered “The Machine Stops.”

The internet is a wonderful tool for doing such research. We know that “The Machine Stops” was originally published in a 1909 journal. I quickly found out it was reprinted in a collection of E. M. Forster’s stories called The Eternal Moment and Other Stories in 1928. “Twilight” was first published in 1934, so theoretically Campbell could have read it. However, I can find no evidence that he had, nor could any of my online chums who were helping me.

Then, when did fandom discover “The Machine Stops” and begin calling it science fiction? There is a wonderful tool called the Internet Science Fiction Database (ISFDB.org) that indexes all it can about published science fiction. It’s entry for “The Machine Stops” is quite revealing, giving a listing of all the times it was reprinted in works related to science fiction.

The first SF anthology that reprinted “The Machine Stops” is The Science Fiction Galaxy edited by Groff Conklin in 1950, and it just so happens I have a copy. It’s a tiny hardback the size of a paperback. Conklin was an early anthologist of science fiction, assembling over forty of them. And there is a clue here to our mystery. In his first three large anthologies most of the stories he collected were from the science fiction pulp magazines. In The Science Fiction Galaxy he begins with three stories that existed before the genre emerged, “The Machine Stops” (1909) and “As Easy as A. B. C.” (1912) by Rudyard Kipling, and “The Derelict” (1912) by William Hope Hodgson. In his previous anthology he had found two pre-genre stories. (Joshua Glenn in recent times has done extensive discovery of stories from this era which he calls Radium Age Science Fiction.)

Conklin never searched hard for these older stories, but other antologists did. See my essay “19th Century Science Fiction Short Stories.” There were plenty of stories published before science fiction was known as a genre that could be called science fiction. I’ve often wondered about the readers who read them. It’s one thing to get a sense of wonder from science fiction in the 20th century, because we had rockets, robots, and atomic bombs to validate our genre’s tales, but can you imagine what readers in the 19th and early 20th century felt when reading their version of science fiction stories?

Scholars have tracked down these old stories, but I’ve never read anything about the readers. I’d love to know the reactions. Did they ever write letters to the editors, or reviews, or even include their thoughts in memoirs and diaries? I can’t find them.

Had science fiction fans discovered “The Machine Stops” before Groff Conklin in 1950? That’s harder to track down but I’ve gotten some help from chums on the net. I believe the trail begins with The Eternal Moment and Other Stories published in 1928. One of those chums named Bill, found these reviews for me:

From an unsigned 13 May 1928 review in the Hartford Courant of The Eternal Moment:

"Here are six strange and striking tales by Mr. Forster, one of the most individual and distinguished of contemporary British novelists . . . "The Machine Stops," which opens the volume, is one of those prophetic fantasies belonging roughly in the same class with certain well-known stories of H. G. Wells. "The Machine Stops" is a ghastly conception, its period set at some immeasurably distant point in an assumed future, when the human race dwells in underground shelters and individuals very seldom see one another; horrible, fantastic and sinister as this story is, it simply follows out, at least along certain lines, the prophecies lately revealed to us in the blinding flash-lights of the Today and Tomorrow Series, and we have already, now in our own existent daily life, attained to some of the wonders which form the abhorrent commonplaces of life in Mr. Forster's fantasy. It may be noted that the fantasy is essential and bitter satire, and that "the machine" does not satisfy every man."

Frank Weir, reviewing in the Decatur IL Daily Review, 8 Jun 1928:

" "The Machine Stops" tells the story of a world inside the earth. Life is controlled by a machine. Forster turns ironical as he presents his travesty on what may be the final result of an age entirely dependent on mechanical genius. Fine writing around an exceptional idea marks this tale as a gem."

John F. Geis in The Brooklyn NY Times Union, 3 Jun 1928:

" "The Machine," which begins the book, is acknowledged an output of two decades ago and portrays the millennium of the electrical age even to the mechanical doctor, but doesn't it sound a bit as though it might be a travesty on birth control? At any rate, the machine, like man, is fallible, and only God reigns omnipotent."

None of those quotes suggest the story is science fiction, but then it was 1928 and the term didn’t really exist. But none of those quotes suggests the story is a different kind of story, or something experimental, or a unique kind of fiction in any way. However, sometime between 1928 and 1950 science fiction fans began to recognize this story as part of their genre.

There are a number of sites that preserve old fanzines digitally, including fanac.org, efanzines.com, and fiawol.org.uk. I’ve discovered that .pdf files at these sites that have been OCRed are indexed in Google. And I’ve also learned that some fanzines are indexed in the many indexes hosted at Galactic Central. Still, with all those sources, and my online helpers, we found very few references to “The Machine Stops.”

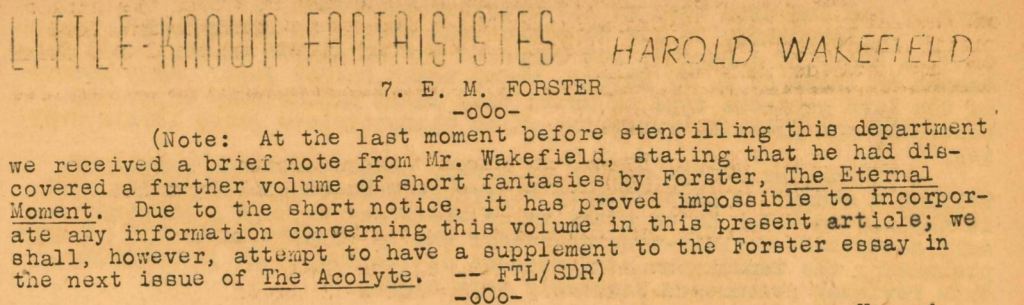

The best reference located was in The Acolyte #9 (Winter 1945), which had a column by Harold Wakefield devoted to finding old pre-genre SF/F fiction called “Little Known Fantasisistes.” The editors said Wakefield had found a copy of The Eternal Moment and Other Stories and would review it in the future. He never did.

We know British fans had a chance to read The Eternal Moment and Other Stories as early as 1937 because a mimeograph bibliography of available science fiction.

Finally, there were references to “The Machine Stops” in Pilgrims Through Space and Time: Trends and Patterns in Scientific and Utopian Fiction by J. O. Bailey, a 1947 book publication of his 1934 dissertation on proto-SF.

Of course, none of these clues proved that science fiction fans read “The Machine Stops” before Conklin’s The Science Fiction Galaxy in 1950 but I imagine that some did. After 1950 the story was reprinted in numerous anthologies, but most importantly in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume 2B (1973) edited by Ben Bova. This was where members of the Science Fiction Writers of America voted for their favorite science fiction stories published before the advent of their Nebula Awards in 1965. To come in at the top of such a poll meant many of those writers knew the story, and probably most, if not all, had read “The Machine Stops” in anthologies since 1950. I can’t prove that though.

“The Machine Stops” has become even more famous since the emergence of the Internet because E. M. Forster in 1909 imagined humans isolating themselves and mainly communicating via a machine. It’s heroine is a kind of blogger. Read the BBC essay, “Did E. M. Forster predict the internet age” or Wired Magazine’s take on the subject.

The story feels like uncanny prophecy. Actually, it’s Forster’s fear about the industrial age completely taking over human society. If you’ve never read “The Machine Stops” you can read it online here or listen to it here:

“The Machine Stops” proves the qualities that define science fiction existed before the label, but I’m also curious if the specific love for such stories existed before fandom?

James Wallace Harris, 8/21/20

The connection to Wells is interesting. I’ve read A Modern Utopia. (It’s dull and there’s really no reason, outside of an interest in Wells or utopias, to read it.) I had no idea Forester’s story was a response to it.

LikeLike

Documenting that is not easy though. I’ve seen mentions of Forster replying to A Modern Utoptia but I don’t have any primary sources. I wish I had a copy of this article, see this abstract.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1468-229X.13022

Wikipedia says Forster was responding to The Time Machine, but I’m not sure about that. It doesn’t document its sources either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately, in the age of the Web of a Million Lies, very few people will dig that deep or look for print sources. Which is why I joked, when I reviewed one particularly obscure book (as far as I know, the only review in English online), that whatever I said, true or not, was going to get quoted.

Don’t know much about Forster. If his letters or journals exist, might be possible to definitively nail down what work Forster was responding to, if any.

LikeLike

I definitely can find places stating “When the Machine Stops” is anti-Wellsian.

Brian Stableford does in Scientific Romances.

John J. Pierce’s When World Views Collide mentions Mark Hillegas The Future as Nightmare: H. G. Wells and the Anti-Utopians (1967) as making the connection between Forster and Wells.

More explicit (unfootnoted) is a quote from Forster in Brian W. Aldiss Billion Year Spree: “a reaction to one of the earlier heavens of H. G. Wells”. No Wells title mentioned though.

LikeLike

Wikipedia quotes that Aldiss quote, and it appears they believe he was talking about “The Time Machine. I’d like to find some of those books you mentioned, thanks.

LikeLike

I suspect it’s sourced in the Hillegas volume — which looks like it’s easy and cheap to buy.

LikeLike

I just wrote a comment for a closed site, which I first copy here; pardon the impersonal tone of voice:

Interesting piece on the reception history of Forster’s “The Machine Stops” within (essentially American) sf fandom. Harris hints that there may have been a readership for the story before and contemporaneous with that sf fandom, and at least one reader comment on his piece cites Brian Stableford’s Scientific Romance book from 1985; hugely expanded as NEW ATLANTIS (2016), it gives several pages to the Forster, primarily in the frame of its original 1909 context.

Stableford does not seem interested in tracing reader reception, relating it solely to the large nest of Scientific Romances of the time, on the apparent tacit assumption that since Forster himself was extremely well-known by 1909, so would this story be (though he was not of course mainly known for short work, his first collection, THE CELESTIAL OMNIBUS, appeared 1911).

The term “scientific romance” was in moderately wide use by 1909, but, unlike “science fiction” two decades later, diffusely. There was no dedicated journal or fandom. So it is sometimes the case that when, in the SFE, we call a book or story a Scientific Romance, we may be retrofitting the term, I think with justice. In recent years I’ve been using the term a lot, and Stableford’s now-much expanded entry http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/scientific_romanceis now linked into (hit Incoming) from around 200 authors. Certainly Wells is central to the term, and Forster is way not irrelevant.

So the history of “The Machine Stops”, well-initiated by Harris, is a long one.

LikeLike

I’m sorry, I don’t have the time to look up specifics right now (will do later today), but Gernsback had a colleague who came to his attention by having assembled a relatively large bibliography of proto-SF and was tapped to continue to provide that service for the magazine. I would be surprised if “Machine” was not gentleman’s bibliography. Can’t remember his name at the moment, but I am also pretty sure that he is mentioned in the Ashley * Lowndes volume you included here. (Or maybe in Westfahl’s The Mechanics of Wonder or Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction.

LikeLike

“The Machine Stops” was written by a british author within the european tradition of SF, which was quite different from that of the magazine-based genre that came to be here in the U.S. in the 1920’s.

It may have connections to _Brave New World_ and/or _1984_ and the popularity they garnered, also authored by british/european authors.

It may have connections to the publishing of _Astounding Science Fiction_ over in the U.K., some of whose readers started communicating with SF readers over here. I don’t know if you’ve read Arthur C. Clarke’s _Astounding Days_ but it’s worth a read for an historian of SF.

LikeLike

This is very interesting. Thank you for your hard work in gathering this information. I find The Machine Stops a fascinating and accurate prediction of man’s future unless some cyber attack prevents it.

LikeLike

The SFE at https://sf-encyclopedia.com/ has an entry on FORSTER https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/forster_e_m which has some information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks.

LikeLike

Even in the 60s the definition of science fiction and fantasy was not as clear as it is today. Maybe you have read The Swords of Lankhmar, by Fritz Leiber. It is a fantasy novel, but it also includes a sci-fi part about a German named Karl, who travel between worlds in the multiverse using a spaceship to collect strange creatures to his exotic zoo. And there are people shrinking and then increase in size again, but to grow they need to replace the atoms they lost when shrinking. Which is more sci-fi than fantasy. Fantasy novels like that are if not absent today, then at least extremely rare. There are of course stories that mix different genres into genres of their own, but I don’t think Leiber and authors like him were thinking like that when they wrote their stories. They simply added what they felt like without being concerned about any “rules” or specific genres.

Like in other genres, science fiction is not just a name, it is also a description. Which probably affects the way English-speaking readers thinks about it. English is not my mother language, and instead of coming up with a “native” name for the genre (a few attempts has been made since, with no success), the same name as in English was used. While I did have English in school, I never really connected the dots before much later in life (like Mr. Smoke-Too-Much in Monty Python): “Hey, it’s the words science and fiction standing next to each other, as in fiction about science”. By when I had already learned to associate the name with a specific kind of stories. There are many attempts to define science fiction, and one of the definitions I like the most is that it is a mental state of mind. So for me, a story was science fiction if it felt like science fiction (and I am most likely far from being the only one). While I have not read many of the old short stories, I have read Jules Verne, Lytton’s Vril and Frankenstein. None of them really feels like science fiction, even if there are science fiction elements present. The oldest story I have read that actually feel like science fiction is Wells’ The Time Machine. Which is probably why many calls him the father of science fiction. The Machine Stops also feels like sci-fi.

So how do English speaking readers (and writers) relate to the name science fiction. It is my impression that some take the name too literally, that the description itself means you as a writer has an obligation to make the story as scientific as possible so it can live up to its name. Many don’t consider Star Wars as science fiction. But I do, for the reasons mentioned above, even if there are fantasy elements present. And personally I would never call the movies The Martian (based on the novel of the same name) or Gravity (with Sandra Bullock) fantasy. Maybe near future techno thrillers or something if one really needs to use a description. It is clearly in the future, and there is a human base on Mars. But they just doesn’t have any sci-fi vibes. Others insist they are science fiction, because science and fiction. In that case many movies and novels dealing with science should also be labelled as that, even if the technology already exist. But that’s just my opinion.

Other genres, like romance and westerns (wild west), speaks for themselves. Even I understood what they meant as a kid.

One (limited) way to find out what other readers felt about popular short stories and novels is to read the stories from readers turned authors after felling in love with what they read. Apparently The Time Machine gave birth to countless similar stories that followed its publication. Time travelers visiting the future and encountering monsters created by evolution. I have not read any of those myself, but I remember an essay claiming this is what happened. The same with Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Vril. An extremely boring novel in my opinion (which makes you curious about the collective consciousness of society back then), but it was so popular that plenty of authors wanted to write their own version of it (and it was included in theosophy and had its own movement), as mention in the intro of The Time Machine: “The influence of the author of The Coming Race is still powerful, and no year passes without the appearance of stories which describe the manners and customs of peoples in imaginary worlds, sometimes in the stars above, sometimes in the heart of unknown continents in Australia or at the Pole, and sometimes below the waters under the earth. The latest effort in this class of fiction is The Time Machine, by HG Wells.” Of course, The Time Machine ended up being way more famous than Vril.

Today the same phenomena, or at least a part of it, exist as online fanfiction.

LikeLike

I always wanted to define “science fiction” in terms of fiction that speculates about science. That it had to accept what science currently knows and then speculate about what things might be possible just beyond the horizon. Most science fiction doesn’t do this.

Science fiction has become a catch-all phrase meaning whatever the individual wants it to mean. However, I believe we can roughly divide science fiction from fantasy most of the time. If it’s about rockets and the future it’s science fiction, if it’s about dragons and the past it’s fantasy. But then you get stories like Dragonflight by Anne McCaffery. However, the first book in the series tries to be science fiction.

LikeLike