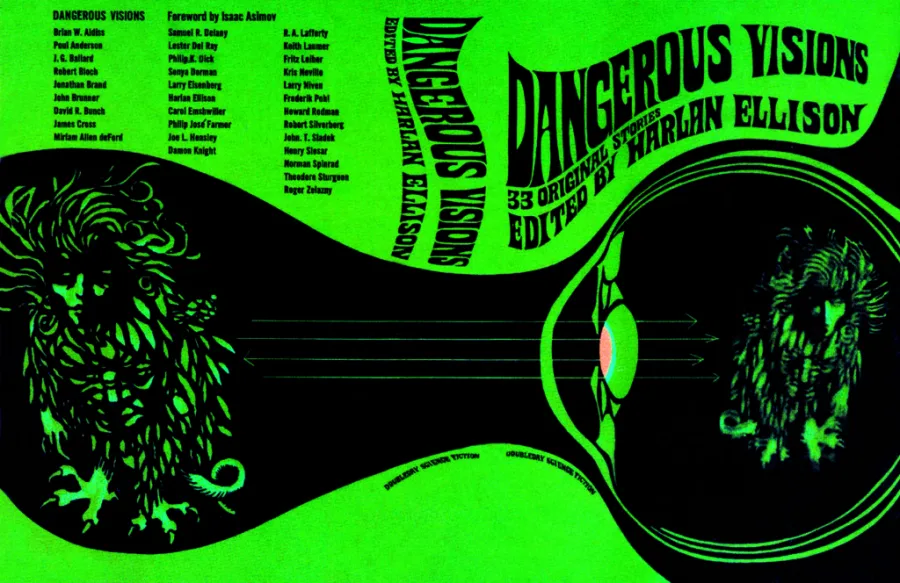

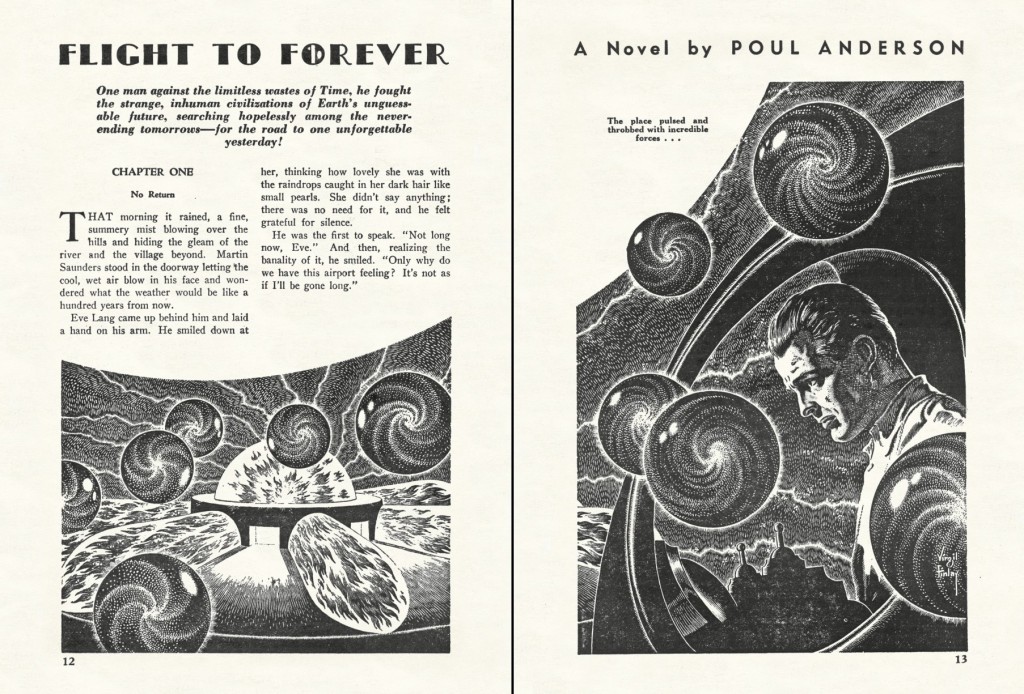

The first story in Dangerous Visions was by Lester del Rey, an old friend and mentor to Harlan Ellison. The second story is by Robert Silverberg, one of Ellison’s best friends from the 1950s. And the next story is by Frederik Pohl, another editor and mentor from the 1950s. I get the feeling Ellison said to all his friends, “Hey gang, let’s put on a show!” (in his best imitation of Micky Rooney from 1939). But “Flies” by Silverberg is one disturbing performance, making me think this anthology should have been called Disturbing Visions.

I thought it interesting in Ellison’s introduction, where he’s bragging what a great writer Silverberg is, and listing all Silverberg’s great works, that none of them were the famous science fiction stories we know today. Then I realized that in 1967, Silverberg had not yet become a famous science fiction writer, the one who wrote the stories we associate with him today. I don’t think anyone will ever list “Flies” as great Silverberg. However, Silverberg would take off in 1967 with his story “Hawksbill Station,” which was a finalist for both the Hugo and Nebula and was anthologized in two best-of-the-year annuals. In the following few years Silverberg would become a giant in the genre.

“Flies” is about an astronaut, Richard Henry Cassiday, who nearly dies in space, but aliens find and repair him. They are God-like beings, who make him physically perfect again. But before sending him back to Earth, they turn up the sensitivity of his brain and fix it so he can telepathically report back to them.

Cassiday returns to Earth and proceeds to track down his three ex-wives. With each, he cruelly hurts them. The story is quite vivid, describing what he does. The alien watchers make him come back to be fixed. On being returned to Earth again, he suffers and reports back on his suffering. We are told that Cassiday is “nailed to his cross.” Are we to wonder if Jesus came to Earth to experience God’s sins against humans? I don’t know.

Cassiday even explains himself by quoting Shakespeare, “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods. They kill us for their sport.” Is Silverberg explaining suffering with theology? Are these two references to religion making the story deeper, or just bullshitting us?

All I know, while reading this unpleasant story, all I felt was horror. Why would Silverberg write such a disgusting tale? Often the stories in Dangerous Visions seem like they were written to top all other stories in grossness. Here’s what Silverberg wrote for his afterward, suggesting the story is about vampirism.

I’ve recently been reading dozens of science fiction stories published before 1930. And one of the most common themes is horror. Before space opera ramped up in the late 1920s, I would say horror was the number one theme of science fiction stories. And if you think about it, horror is still a common theme. A thrilling alien invasion film like Independence Day is full of horrible things happening to people — but the peak thrill of the film is when we do horrible things to the aliens. Isn’t science fiction often being Romans at the Colosseum?

Kurt Vonnegut had advice to budding writers, “Do mean things to your protagonist.” We love characters who overcome adversity. But do we love characters who create adversity? I’m reminded of “Fondly Fahrenheit” by Alfred Bester. In that story, James Vandaleur and his android servant kill people, even children, in horrendous ways. That’s one of my all-time favorite science fiction short stories. But it didn’t disgust me. Why?

One of the reasons why I’m reading all those old pre-1930 science fiction stories is because it shows that science fiction stories were inspired by previous science fiction stories, and if they are successful, inspire later science fiction stories.

Here’s my problem with Dangerous Visions. I can find antecedents for its stories, but I’m having trouble finding stories that DV inspired in the years since. For all its success, Dangerous Visions is a kind of dead end, at least so far in my reading. Is that because science fiction as a genre decided to head off in another direction after Dangerous Visions? Probably not, probably I just can’t recall stories that follow the trajectories of DV stories. Maybe DV taught me to avoid them.

But so far, Dangerous Visions feels like a combination of the 1969 rock festival at Altamont and Charles Manson. Those were two years into the future. Maybe DV was being prophetic.

I thought I’d add this review of Dangerous Visions.

James Wallace Harris, 5/11/24