Group Read 27: The Big Book of Science Fiction

Story #16 of 107: “Desertion” by Clifford D. Simak

“Desertion” and its sequel “Paradise” are from the 1940s, the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction. They are also the middle stories from the classic science fiction fix-up novel City. “Desertion” was published in the November 1944 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, and “Paradise” in the June 1946 issue. If you haven’t read the stories please go read them now because I need to write about the details of each to make my point and that will give away major spoilers.

“Desertion” is the perfect story to make my case that 1940s science fiction was often about the next evolutionary step for our species. In a way, John W. Campbell, Jr. could be considered the Ralph Waldo Emerson of a 20th century transcendentalism, but we call it science fiction. I say that because many science fiction stories from the 1940s and 1950s were about breaking on through to the next stage of human existence. Maybe this desire was inspired by the actual horrors of WWII or the dreaded fears of Doomsday felt during the Cold War. Was science fiction our collective unconscious merely telling us we need to change before we destroyed ourselves and the planet? Or was it just another theme the science fiction muse has always entertained?

The VanderMeers did say in their introduction, “City was written out of disillusion…seeking after a fantasy world that would serve as a counterbalance to the brutality through which the world was passing.” That might be the realistic take on science fiction, that it offers fictional escape from reality, but growing up I believed science fiction’s purpose was to inspire us to create the futures we wanted to build, and divert us away from the futures we feared. In my old age science fiction has become my escape, my comfort food, but when I was young I believed in the potentials it promised. I have to wonder if young readers today find the genre a fiction of escape or hope? But even the one utopian Star Trek is now is about endless conflicts.

In “Desertion,” Kent Fowler has sent many men to their apparent death trying to colonize Jupiter by downloading their brains into genetically engineered creatures modeled on Jovian lifeforms that can survive the harsh conditions of Jupiter. The idea of adapting the human form to an alien environment is called pantropy, and “Desertion” is one of the early examples of the idea being used in science fiction. However, Simak takes the idea even further when Kent Fowler and his dog Towser are converted into the Jovian Lopers. Fowler just couldn’t ask another man to volunteer, so he underwent the process himself and taking his old dog with him. As Lopers, Fowler discovers that Towser is more intelligent than he ever imagined when they begin telepathic communication. The reasons his men never returned to the dome after being converted to Lopers was their minds expanded into a new stage of awareness and they couldn’t stand downgrading into human form again.

Five years later, Fowler does return to the dome in the story “Paradise.” He feels its essential that he let his fellow humans know about this greater stage of consciousness. In this story though, we also learn humanity is facing another crisis point in their development. Superior humans called mutants also exist, as do uplifted dogs, and intelligent robots. When Fowler tries to spread the word that paradise can be found on Jupiter, his message is suppressed by Tyler Webster who wants humans to stay human. Webster pleads with Fowler to withhold knowledge of the heaven on Jupiter because he fears all humans will rush to attain instant resurrection (my words).

“But I want you to think this over: A million years ago man first came into being—just an animal. Since that time he had inched his way up a cultural ladder. Bit by painful bit he has developed a way of life, a philosophy, a way of doing things. His progress has been geometrical. Today he does much more than he did yesterday. Tomorrow he’ll do even more than he did today. For the first time in human history, Man is really beginning to hit the ball. He’s just got a good start, the first stride, you might say. He’s going a lot farther in a lot less time than he’s come already. “Maybe it isn’t as pleasant as Jupiter, maybe not the same at all. Maybe humankind is drab compared with the life forms of Jupiter. But it’s man’s life. It’s the thing he’s fought for. It’s the thing he’s made himself. It’s a destiny he has shaped. “I hate to think, Fowler, that just when we’re going good we’ll swap our destiny for one we don’t know about, for one we can’t be sure about.” “I’ll wait,” said Fowler. “Just a day or two. But I’m warning you. You can’t put me off. You can’t change my mind.” “That’s all I ask,” said Webster. He rose and held out his hand. “Shake on it?” he asked. Simak, Clifford D.. The Shipshape Miracle: And Other Stories (The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak Book 10) (pp. 83-84). Open Road Media. Kindle Edition.

“Desertion” is also an early example of mind uploading, a very popular theme in science fiction today. “Desertion” and “Paradise” also assume there would be life, even intelligent life on every planet of the solar system. The City stories are extremely positive about human potential. The collected motif of the City stories is humans have left the solar system and only intelligent dogs and robots remain to remember them, to tell their story. Childhood’s End used that theme too, about humanity leaving Earth for a new stage of evolution.

“Paradise” is also an early story about mutants. After Hiroshima, people feared radiation would create mutations that were either monsters or an evolutionary superior species. In “Paradise,” the mutants are that superior species, ones who are waiting for normal humans to get their act together. Mutants arrange for Tyler Webster to get a kaleidoscope that will trick his brain into opening its higher functionality. The kaleidoscope is like the toys from the future in “Mimsy Were the Borogoves” that trigger evolution in normal human children. Also within the same story is the idea that Martians had developed a philosophy that could trigger evolutionary uplift. Heinlein also worked this theme in Stranger in a Strange Land (1961). Sturgeon’s classic fix-up novel, More Than Human (1953) deals with mutants with wild talents, and the evolution of a gestalt mind. But this theme was repeated countless times in 1940s and 1950s science fiction.

In other words, “Desertion” is one of the bellwether stories our genre.

There used to be a common pseudo-science belief that humans only used 10% of their brains and we have the potential to unlock the mysterious 90%. This was a common myth in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, and probably went back decades and decades. I just checked Wikipedia and found they had an entry on “The Ten Percent Brain Myth” that even mentions John W. Campbell.

A likely origin for the "ten percent myth" is the reserve energy theories of Harvard psychologists William James and Boris Sidis who, in the 1890s, tested the theory in the accelerated raising of child prodigy William Sidis. Thereafter, James told lecture audiences that people only meet a fraction of their full mental potential, which is considered a plausible claim.[5] The concept gained currency by circulating within the self-help movement of the 1920s; for example, the book Mind Myths: Exploring Popular Assumptions About the Mind and Brain includes a chapter on the ten percent myth that shows a self-help advertisement from the 1929 World Almanac with the line "There is NO LIMIT to what the human brain can accomplish. Scientists and psychologists tell us we use only about TEN PERCENT of our brain power."[6] This became a particular "pet idea"[7] of science fiction writer and editor John W. Campbell, who wrote in a 1932 short story that "no man in all history ever used even half of the thinking part of his brain".[8] In 1936, American writer and broadcaster Lowell Thomas popularized the idea—in a foreword to Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People—by including the falsely precise percentage: "Professor William James of Harvard used to say that the average man develops only ten percent of his latent mental ability".[9]

The belief was based on the logic that feats of human endurance and mental powers have been displayed by Indian fakirs, hypnotists, yogis, mystics, tantric masters, psychics, shamans and other outliers with esoteric knowledge, and that proves we had all untapped potential. Science has since shown that we use 100% of our brains, and disproved all those pseudo-scientific claims.

Yet, back in the 1940s science fiction writers and readers, and especially John W. Campbell, Jr. believed humanity was on the verge to metamorphizing into Human 2.0 beings. That’s what “Desertion” and “Paradise” is about, and you see that same hope in so many other stories from the 1940s and 1950s. It’s also why John W. Campbell, Jr. and A. E. van Vogt went gaga over Dianetics in 1950. Please read Campbell’s editorial and L. Ron Hubbard’s article on the subject in the May 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. We look down on Campbell today for believing in this malarkey, but Dianetics reflected the promise of all the stories he had been publishing. Campbell was desperate to quit promoting fairytales for adults and find an actual portal into the future then and now.

Sure, science fiction is fun stories set in the future, often about space travel, aliens, robots, and posthumans, but it also connects to real hopes and fears. The belief humans could transcend their present nature is a fundamental hope within the genre. A modern example is The Force in Star Wars, or the discipline of Vulcans in Star Trek. Clifford Simak spent his entire career writing stories about people who transcend our ordinary consciousness. And is this so weird and far out? We Baby Boomers dropped acid in the 1960s chasing higher states on consciousness, then in the 1970s we pursued all kinds of New Age therapies and ancient spiritual practices. Of course, since the Reagan years of the 1980s we’ve come down to Earth accepting human nature for what it is. We’ve stopped looking for transcendence and scientific utopias, accepting our normal Human 1.0 selves that pursue wealth, power, conquest, war, and commercialization of space and the future.

Reading the best science fiction stories of the 20th is a kind of psychoanalysis of our expectations about the future, both good and bad.

The anthology which up till now has been the gold standard for identifying the best science fiction of the 1895-1964 era is The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One which contains short stories, and the supplemental volumes Two A and Two B which contain novelettes and novellas. Volume One holds the top spot at “Best Science Fiction Anthologies” at Listopia/Goodreads. The stories were selected by members of Science Fiction Writers of America in the 1960s to recognize science fiction published before the Nebula Awards began in 1965.

In recent decades I’ve encountered many a science fiction fan who wondered what the table of contents would be to an updated Science Fiction Hall of Fame volume for 20th century science fiction if SF writers voted today. Any retrospective SF anthology that covers the 20th century is essentially competing with that wish. “Huddling Place” another story from Simak’s City was chosen for The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, but I’ve known many fans who thought they should have picked “Desertion.” Events in “Huddling Place” are referenced in “Paradise.” But if you look at the table of contents for the volumes One, Two A, and Two B, you’ll see several stories about next stage humans.

- “Mimsy Were The Borogoves” (1944) – Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

- “Huddling Place” (1944) – Clifford D. Simak

- “That Only A Mother” (1948) – Judith Merril

- “In Hiding” (1948) – Wilmar H. Shiras

- “The Witches of Karres” (1949) – James H. Schmitz

- “The Little Black Bag” (1950) – C. M. Kornbltuh

- “Surface Tension” (1952) – James Blish

- “Baby is Three” (1953) – Theodore Sturgeon

- “Call Me Joe” (1957) – Poul Anderson

- “Flowers for Algernon” (1959) – Daniel Keyes

- “The Ballad of Lost C’mell” (1962) – Cordwainer Smith

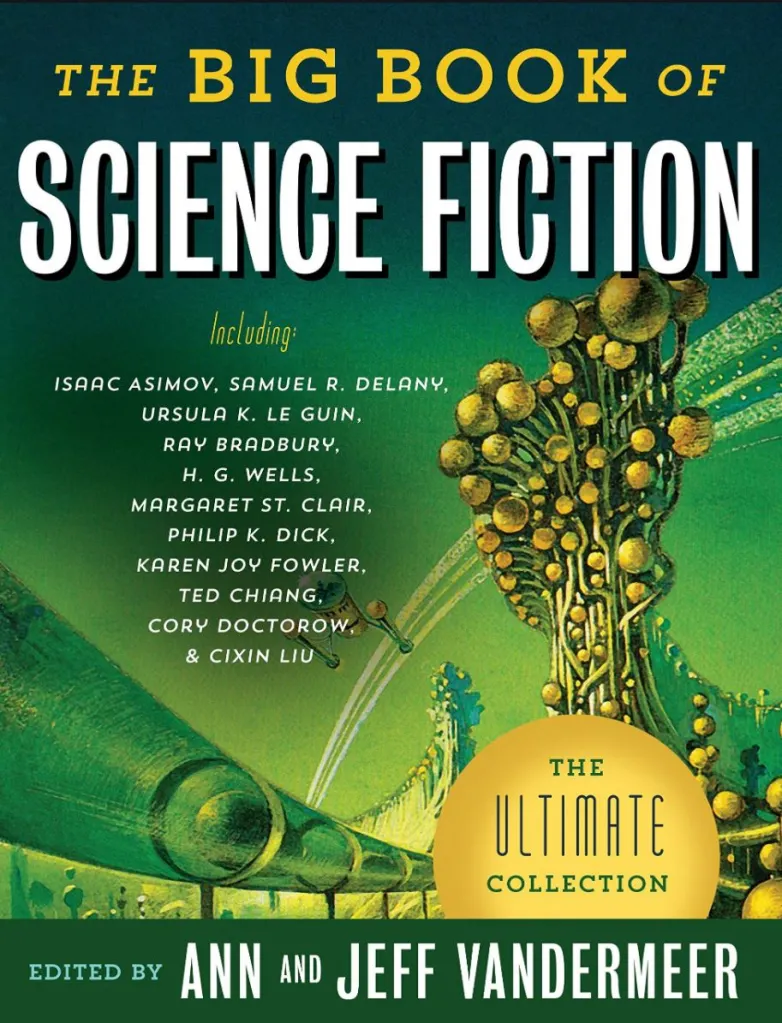

The Big Book of Science Fiction covers the same territory as The Science Fiction Hall of Fame volumes, and there is some overlap of contents, but I think it features less of the transcendental science fiction I’m talking about here. Maybe it’s stories are more realistic, but we have many stories to read before we know. But the acceptance of our existing human nature is understandable, because we don’t believe in those kinds of hidden talents anymore. Well, at least most scientifically minded adults. Wild talents and mutants have become the staple of comic book fiction. We have demoted those hopes to the level of children’s power fantasies.

I’ve often said science fiction beliefs replaced religious beliefs in the mid-20th century, and maybe now we’ve become atheists to science fiction too. If you doubt my assertion the SF replaced religion just think of Fowler as Jesus. He had died and was resurrected into a new life in heaven, and his soul has been expanded with great spirituality.

I even wonder if the VanderMeers included “Desertion” and “Surface Tension” for their use of the pantropy theme rather than psychic potential theme? Science fiction has given up on quickly evolved humans, and instead promotes technical transhumanism and genetically engineered Human 2.0 beings.

“Desertion” was probably a Top Ten story when I was young, and it’s still a 5-star favorite in my old age. But I now know there is no life on Jupiter and Mars, and I will never find the kind of transcendence that Fowler and Towser found. NASA probes have shown the solar system is sterile rocks, and nothing like what Simak imagined. Oh, we still hold out for life on Titan or some other moon’s deep ocean, but I doubt we’ll find it when we get there. Thus “Desertion” has become a fond fantasy from my youth, sort of like Santa Claus.

James Wallace Harris, 9/18/21

Update: I remember people saying we only use 5% of our brains, but research shows the figure used was 10%, so I made that change. I also found the quote from Wikipedia attributing Campbell to promoting the idea.

Wow, what an elaborate analysis! No wonder, as it’s a masterpiece for you, and we love to talk longer about our darlings, don’t we? 🙂

I only recently learned about Emerson, and transcendentalism in general. Not that I’m not acquainted with philosophy, but Emerson and Thureau are specifically U.S., they don’t appear here in Germany.

Every time I hear Dianetics or that “you only use 5%” marketing by Scientology, I feel like projectile vomiting. Sorry, can’t help myself there. Maybe that’s a reason why I’m sceptical about 1950s SF, or maybe I’m overgeneralizing.

You already read my own review of this story. I liked it, but it’s not a favorite. It’s one of the better stories of that time, for sure.

LikeLike

Andreas, the 5% theory was common and not exclusive to the Scientology crowd. It’s very hard for the young to understand that people in the past thought differently. I can understand why you want to vomit at the idea today because we think so differently, but back then a lot of people loved the 5% theory. There are people who still believe in it. I’m 70 which makes me old enough to remember, but Simak and Campbell were from an even older generation, even a generation before my father, and I have a hard time fathoming their headspace. I know they had a hard time understanding my crowd that came of age during the 1960s.

Yes, we do like to talk more about our darlings. And I can understand why younger people will be less impressed with “Desertion.” Science fiction changes over time, just like popular music. Science fiction in the 1940s had a revolutionary flavor, somewhat like rock music had in the 1960s, but I’m not sure modern minds can detect it now. And 1950s SF is more akin to the music of the 1970s when things got more elaborate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vomiting has more to do with Scientology.

I just asked around at my mother and my parents in law, who are all 85 years old. None of them ever heard of the 5%. No, that’s not representative, but maybe it’s a US idea? I only have seen it as Scientology advertisements, back in the 80s.

LikeLike

That’s interesting. Maybe it was just an urban myth in the U.S. Well, I just checked good old Wikipedia. Evidently, it was more common to say we used 10% of our brain. They trace the idea back to William James. And they even quote John W. Campbell.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_percent_of_the_brain_myth

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jim, I strongly suspect that “Desertion” received more votes than “Huddling Place” in the SF Hall of Fame voting. It’s one of the cases in which Robert Silverberg consulted with the author before deciding which story would be included. “Huddling Place” and another story finished close in the voting, and the other story was slightly ahead. But both author and editor preferred “Huddling Place”, so that was the story that was included. Robert Silverberg has never revealed what the other story was, but in view of its fame and reprint record, it was probably “Desertion”.

LikeLike

I’m also partial to “Huddling Place,” as Paul knows since we argue over which is better. But I love “Desertion” too. “Huddling Place” is a more sophisticated story. “Desertion” is almost pure emotion, yet I have to admit I found a lot more in it when I read it this time.

It’s been years since I’ve read City, and writing this review made me see things Simak was doing in that series of stories that I think I missed before. I need to reread it. Simak was doing more than just telling stories and it’s why a collection of stories can work so well as a fix-up novel.

LikeLike

One of the classic stories, I was thinking of having as the next group read on Classic Science Fiction & Fantasy Short Stories, for awhile.

Now it will be. I’ll comment here after reading it.

https://groups.io/g/classicsffantshortfic

LikeLike

For people who do not like Facebook, William moderates a listserv that discusses short science fiction. Follow the link if you’d like to discuss short SF via emails.

LikeLike

I reminds me of “The Dance of the Changer and the Three” by Terry Carr and “Noise” by Jack Vance. Humans’ fundamentally anthropomorphic (and therefore limited) way of perceiving things. Very interesting story.

LikeLike